Coco, fast becoming a favorite medium for crop production worldwide, is still relatively new to the industry. While brought to the attention of the Royal Horticultural Society in the 1800’s, it was not until the late 1970’s early 1980’s that it began to carve a niche for itself. Its difficulties in getting started were due to a lack of understanding of both the chemical and physical properties of the product. Once the properties of coco as a medium were understood, and the correct way to treat coco, popularity of this medium for growing has taken off. What are some of these issues? What follows is a brief discussion of some of the issues with coco and their possible solutions if needed.

Some basic properties to be aware of

It should be understood that coconut trees are capable of ‘drinking’ sea water because they have developed the ability to concentrate excess ions in the areas surrounding the cells that give the appearance of a high interior plant EC which then allows osmosis to continue moving water into the plant from the high EC sea water. In so doing, it is this attribute that gives both positive and negative characteristics to the use of coco as a plant growth medium.

This attribute also allows the husk tissue to be very stiff and slow to decompose so that it is able to protect a developing embryo and future tree as it floats around the ocean for a long period before germinating and landing on a new beach. In so doing, it allows the coco tissue to have both a known content and a known path for decomposition of acceptable duration, enabling the development of a system for usage. It also allows for a known structure to exist for a known amount of time giving the physical attributes necessary of a good medium.

These physical aspects include fibers and a breakdown product known as coco peat. The husk of the nut, once the food part is removed, is softened then the fibers are torn from them. This results in the long fibers that are used in very stiff applications from door mats to brooms, and shorter fibers that provide a ridged structure form, giving the coco the characteristic porosity. Also, the dust or coco peat is released; this being a smaller particle that resembles a sponge. The coco peat part not only aids in structure, it also supplies a great amount of water retention. After a proper amount of time being composted and worked by movement and rinsing, the consistency reaches its best and is of a more stable chemistry within the boundaries for use in growing. Still, the chemistry is not fully correct and must be adjusted.

Once the husks begin soaking and are torn apart, the decomposition process accelerates for a time. Those concentrated ions (salts) begin to be released at a very fast rate. Careful working and the right amount of time controls this until the rate of release falls into acceptable bounds which can be used to structure a system for growing. In the process of this breakdown, the sites that release the ions such as Potassium, and Sodium, remain and function as a Cation Exchange Site (CEC) to which a usable plant nutrient can be attached as is possible in good mineral soils. At this point, the medium needs to be processed by buffering the medium with product designed to control the pH and protect the important ratios required to keep these elements available to the plant. This is as mentioned in the previous article on page 4. These excess ions or salts are released as long as coco decomposes and must be dealt with at all times.

The important considerations for a correctly designed coco media for use in growing includes:

- Correctly handled coco of a consistent quality in both chemistry and physical structure.

- Properly aged to develop peak efficiency and quality of the product.

- Correctly balanced by buffering designed for the characteristics of individual batches of ready product.

- The availability of a nutrient designed to both feed the plant and continue to control and adjust the continuously decomposing coco medium.

While there are more things to consider, these are important to remember for the rest of this story.

Producing a good-quality coco substrate is an intensive process that takes months. To be able to use the product as a growing medium, the substance derived from the coco husks needs to be aged, washed, treated and rinsed. If this process is not carried out, or not carried out correctly, there is a risk of lacklustre growing results or potassium or calcium deficiencies.

Once this process has been completed, the coco has to be dried so that it can be pressed and made ready for shipping. The drying process is obviously dependent on the prevailing weather conditions, so good producers will ensure that they have enough coco product stocked up to see them through the rainy season or any shorter wet periods. Producers also need to take precautions against the risk of impurities or inadvertent contamination. For example, the coco is susceptible to contamination with (tropical) weeds or human pathogens, or it could become mixed with coco that has not yet been aged or other substances such as sand. Any of these impurities could cause problems when the product is used for growing.

To prevent contamination, good coco producers will take steps to protect the coco as it dries, such as using protective screens, cleaning the drying area, checking samples of the product in a laboratory, using storage facilities and following appropriate procedures. The two photographs above (Picture 1 and Picture 2) show examples of good and bad drying areas – on Picture 2 you can see a drying area where effective precautions have not been taken, meaning that the chance of impurities is much greater. On Picture 1 you can see a concreted drying area where the risk of contamination with impurities is being minimized.

Specific issues addressed in coco – simple problem solving

Using the correct coco as a medium can ensure some pretty exceptional results, the reasons for which are not all clearly understood. Research into the properties processed in coco continues every day. Faster growth, healthier plants, lush quality, and adaptable medium are all used to describe successful trials in the product. It has long been known and recently substantiated, that coco as a medium promotes health by specific factors found in the product and by the micro-flora and fauna that develop in coco. It provides a very free availability of applied nutrients by not binding or affecting the applied nutrients. It also provides pH control without additional liming requirements across successive crops. Yet it will do none of these without correctly buffering the coco before use. After that, the buffering is best maintained over time by the correct type and use of an applied nutrient.

Using bad coco is the start of a recipe for disaster and hard work. Incorrectly sterilizing the coco by harsh steaming or toxic chemicals destroys the characteristics of the product. Not rinsing before packaging, or poor rinsing (too little or bad water) leaves behind high salt levels. Failing to properly buffer leaves big holes in the chemistry of the medium. Green or old coco is equally problematic and inconsistent in the way it is built and what the end results will be from wildly fluctuating EC and pH to rapidly changing and poorly built structure. Salts are given off all the time (such as Sodium, Potassium, and Chlorine) and must be removed or their effects neutralized. Much goes into the successful application of using coco as a growth medium.

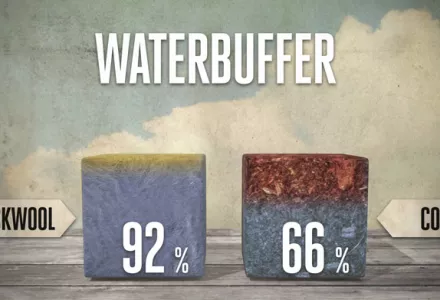

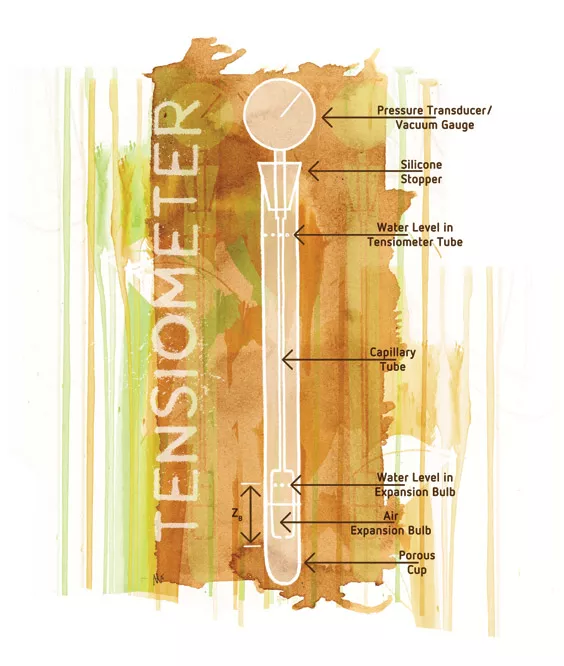

One of the biggest issues with coco is watering practices. Coco is a sponge, and like a sponge, when squeezed water comes out, but not all the water. The sponge will remain damp and coco can still appear wet without having enough available water to give to the plant. Constantly watering coco results in over-watering. When using coco, there is a need to water at a minimum of 50% dry. Sometimes 70% dry might be better especially during the first weeks, when most roots are formed. After all, the roots also need oxygen and where there is water there is no air. A sophisticated and reliable method to measure the plant available water in the coco substrate is a tensiometer (pictures 3 and 4). It is a device that determines the water potential in a substrate, effectively the force needed to release the water from the substrate. This ‘force’ is minimal in a water saturated substrate and maximal when the substrate is completely dry.

There is an easier and cheaper way to determine the amount of water available to your plants. Determine plant available water weight by thoroughly watering a container with plant and coco and weighing it after drain. Allow the plants to dry down until they reach wilt point and weigh again. The difference in weight is the available plant water. When 50 - 70% of this amount is used from the container, it is time to apply water again. It is never good to wilt a plant but an experimental plant might be in order. If plain water is used on established coco, the buffer will be upset and the next issue surface.

The chemical balance in the coco is critical in 3 basic ways. First the pH of the coco as a natural product is not ideal and must be adjusted. Second, the CEC spoke of earlier are not real CEC in the classic sense, because while they will loosely hold monovalent cation elements (ions with a single positive charge) on a matching negative charge, they bind more tightly a divalent ion such as Calcium or Magnesium making them unavailable to the plant, and they come and go as decomposition moves forward. Third, the give off of other ions by coco degrading upsets the ratio of the elements to each other causing many to become unavailable. The established buffer spoken of temporarily fixes this issue by filling the sites with divalent elements while stabilizing the pH at the range desired and setting the correct ratio of elements to each other.

When the water used to mix nutrients is very soft, then the concentration of nutrients has to go up or the coco will rob the nutrients and a Calcium deficiency will begin to show. This is exactly due to these issues. With the popularity in Reverse Osmosis systems sky-rocketing, this issue is seen more and more often. Growers plan to use pure water, feed lightly to avoid burn and feed often to keep things pumping. This however is avoidable by adding back some of the original water to buffer the water once more. There is no other very effective cure and the throwing of a Calcium/ Magnesium product at the problem gets worse over time. Adding a higher EC of the nutrients is a better and safer option.

Most importantly, the buffering done to coco puts what could be considered a coating on the coco that allows the coco to only show the correct pH and does not interfere so much with availability of nutritive elements. The coco is always changing as it decomposes and the coating must also change and repair. The nutrients designed for the coco are critical in this effort and maintenance of the buffer. Any other ratio and composition of nutrients will not hold the buffer, including plain water which makes the coco EC drop and the buffer disappear. Equally important is following the correct feed chart and testing coco correctly.

Standards are not absolutes but markers by which things are measured. A foot is a foot because it is known as a meter is a meter. In order to get the true picture of the condition of coco in EC and pH, it only works correctly one way and that is by the correct extraction method with Barium chloride in water. Barium, a bivalent metallic alkaline earth metal, strongly binds to the coco surface releasing virtually all previously bound cations: sodium, potassium, calcium, magnesium and ammonium if present.

The level of cations in a barium chloride extract is a good measure of the substrate quality at that very moment and a prediction of nutrients that were about to be released by the coco substrate making them available to the plants.

Measuring drainage or run-off alone will never be accurate. It may give the grower an idea based on experience but that is all. Knowing is growing and correctly measured coco should match the characteristics described.

Additionally, some issues or questions seen in the use of coco includes Nitrogen binding and ways to increase aeration. Many growers enjoy using coco more than once, but for successful growth, the coco has to decompose a certain amount before the next crop. If the first crop fails or is too fast, then Nitrogen will tend to bind in the coco and availability delay causing a week or so of Nitrogen deficiency symptoms to appear.

Finally some growers insist on adding perlite to the media to ‘loosen’ it. Perlite is about identical to coco in physical characteristics and is not liable to do anything for porosity but will affect the chemical profile.

In the end, it is probably best to find a company with decades of research into coco, that provides correct solutions, and that introduced coco use into this market. Trust in the experience, use quality products that are well researched, and keep it simple.